Designing for PBSA: In Conversation with Jasper Sanders, Jasper Sanders + Partners

Jasper Sanders is the Founder and Director of Jasper Sanders + Partners, an award-winning, Manchester-based space innovation studio known for redefining how people live, learn, and interact within the built environment. Since 2013, Jasper and his team have delivered market-leading interiors across the UK, with a particular focus on commercial residential projects, including Purpose-Built Student Accommodation (PBSA), Build-to-Rent, and Co-Living schemes.

These sectors sit squarely between commercial design, including considerations for hospitality, workplace, and care, and residential design. They include extensive amenity spaces that foster community while balancing operational efficiency with the warmth and comfort of home.

In this exclusive interview, Jasper explores the evolving world of PBSA design, sharing why the sector’s growth offers creative opportunities for designers, what distinguishes PBSA interiors from other sectors, and how his team prioritises wellbeing, sustainability, and adaptability to create spaces where students can thrive.

To start, could you introduce yourself, your role at Jasper Sanders + Partners, and your studio’s approach to designing spaces for people?

My name is Jasper Sanders and I’m the Founder and Director of interior design studio Jasper Sanders + Partners. I launched our Manchester-based business in 2013 and, over the last decade, we’ve established ourselves as a leading, award-winning space innovation studio.

Our projects span the UK, including recently completed schemes in London, Manchester, Liverpool, and Edinburgh. Our principal work sector is commercial residential, incorporating BTR, Co-Living and PBSA interiors, with a strategic aim to define and deliver market-leading brand and interior identities through a commitment to innovation and the reinvention of architecture from the inside out.

Changes in student social habits – the new focus on self-improvement

Purpose-Built Student Accommodation (PBSA) has grown rapidly in recent years, offering students dedicated housing with modern amenities and unique features. Why do you think this surge in demand has occurred, and what creative opportunities does it bring for designers like yourself?

The reasons behind the surge in demand are three-fold. First, undergraduate students often have to live out for part of their degree and the quality of existing private landlord property was highly variable, to say the least, so the opportunity was ripe for something better.

The second critical factor was a change in attitude from students, and their parents, once tuition fees were introduced in 1998. Students became consumers and paying tuition fees raised their expectations.

The third influence was building regulations, which spell out what new-build living spaces need to include in terms of minimum space requirements, but which allowed compact spaces to be delivered in the PBSA and Co-living sectors, when combined with communal amenity provision.

We always design amenity spaces on our PBSA projects – and mostly the rooms too. It’s interesting to work with young people and to address both their current needs and social changes. As an example, in the early days of designing PBSA, there was a much greater focus on drinking culture. We used to design huge glass fridges for people to buy cheap alcohol for ‘pre-loading’ sessions before a night out, but those days are gone. Post-graduate and international student requirements, as well as changing social mores, now see a greater focus on hydration, gym habits and general self-improvement. Our focus is always on how our designs can support students as they aim for academic success and to create the best spaces for them to work, rest and play in.

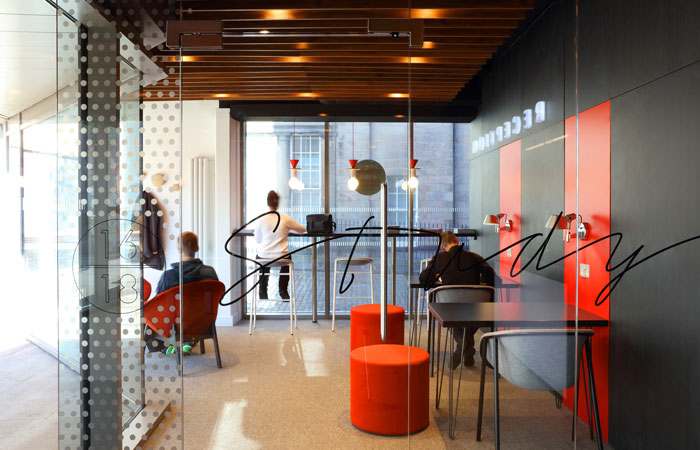

A successful amenity is a flowing series of spaces, connected through glazing

What do you think distinguishes PBSA design from other sectors of architecture and interior design, and what are the key challenges you face when creating spaces specifically for student living?

You’re designing for a very particular demographic in this sector first of all. Additionally, schemes tend to be close to universities and city centres, meaning the land value is high and there’s a remit to get the maximum number of apartments out of a given plot, whilst in BTR larger apartments are required, so it’s less efficient to plan BTR schemes on sites where space is more limited.

The key challenge is often dealing with what’s left behind by a scheme’s architects on a new-build, who tend to focus on the exterior and a building’s form and mass. We inherit plans with functional labels on rooms with little connection or overlap of activity, whereas a successful amenity area is a flowing series of spaces, connected through glazing, light and glimpsed sightlines. Students perceive amenity spaces as a single destination, so we have to work very hard to shape space to work well to deliver the right experience.

Each material and product choice is validated to ensure both low carbon and minimised impact upon environment.

What sustainability accreditations do developers and operators typically seek for PBSA projects, and how does your design team work to meet and exceed these requirements?

This may be a surprising answer, but sustainable accreditations for interior designers are very rarely part of the brief. This doesn’t mean they aren’t on developers’ agenda – just that they tend to fall more into the architectural remit.

Our work on sustainability is therefore mostly self-guided, first by creating efficient spaces, then by validating each material and product choice to ensure both low carbon and minimised impact upon the environment. We would like more environmental data from sustainability consultants on all products, but there’s rarely any budget to appoint someone.

Jasper Sanders + Partners always design a variety of settings, so that people can be at ease alone or with one other person

How do you ensure that the spaces you design address the physical and mental wellbeing of users, while also incorporating accessibility and neuroinclusive principles to cater the user’s needs?

We have always been very aware of the need to make places feel both safe and accessible for all. This sensibility began with being particularly aware of women’s priorities, including the ability to be able to see into darkened spaces before entering and creating circulation spaces wide enough for people to pass each other without touching.

We’re also very aware, like any responsible design studio, of all accessibility requirements, whether physical or visible. We consider graphic design and colour index choices very carefully, for instance. For us, the key neurodivergent design principles relate to lighting, which needs to be subtle, flexible and relating to the mood or time of day for each particular space – plus acoustics. There’s nothing more disruptive than sounds that rattle, grate or echo when you’re trying to concentrate!

We also think hard about sociability, both in terms of those who want to be social and those who want to be around sociable areas, but a little set apart, making sure there are always a variety of settings for people to be at ease alone, with one other person or in small or larger groups.

People-watching and engaging with users on site allows for informal evaluation of how a project is used by the design team

How do you gather data and feedback on the requirements of space users to inform the design process, and how do you evaluate the success of the spaces post-completion?

Operators tend to have fairly sophisticated questionnaires for assessing user feedback, which are sent out halfway through the academic year. These are not, however, necessarily shared with the design team or particularly relevant – tending, like TripAdvisor reviews, to focus on issues outside the scope of interior designers. Some developers do call in consultants for more specific research, but that takes place more rarely unfortunately.

We’ve taken to evaluating informally instead when we visit sites for photo shoots or other marketing-related activities. We sit and people-watch and we talk to absolutely everyone we come across, but especially front desk, as the reception team see across the whole operation. This gives us a good first-hand sense of how a building is being received, which areas are being used the most and any potential issues.

Jasper and his team believe strongly in the power of colour in their schemes

What do you, as a designer, need from commercial interior suppliers to ensure the success of PBSA projects? Are there specific innovations, materials, or qualities you believe are still missing in the market?

A much more straightforward way to find out how sustainable a product is. I’d love to see a simple traffic light system or a regulated panel, as in the food industry, where you can get the equivalent of the calorie content, full ingredients and percentages of fat, protein etc. There are lots of different certifications, but that only presents the problem of how to compare. An industry standard is badly needed. We end up putting our trust in certain suppliers we know are serious about sustainability. Good examples for us are Forbo and Ultrafabrics.

One aesthetic request is for more colour choice. The narrowing of choice is really limiting. Colour is so powerful and the current trend for neutral tones (Millennial Grey) suggest caution around colour – or even outright fear of colour (chromophobia). These are not positive for our collective psychology.

Fewer international students are now coming to the UK

Finally, with PBSA continuing to evolve, how do you see the sector changing over the next decade, and what shifts do you think will define the future of student accommodation design?

I think it’s sensible not to predict too much because the most major changes are often unpredictable. Events of recent years, from the pandemic to Brexit, have taught us that!

However, from what we’re seeing now, I’d say that the great new-build era is slowing. We’re certainly seeing developers being more cautious and holding back, waiting for business rates to be more favourable. At the same time, fewer international students are coming to the UK and the Chinese market in particular is beginning to diminish. Degree apprenticeships are becoming a popular alternative, which will see more young people living at home and studying part-time. AI will inevitably affect the job market, leading to increased caution about investing in tertiary education.

The one positive in this for interior designers is that refurbishments are often more successful design solutions. On a new-build, the budget can be diminished post-architecture and construction costs, whereas a refurbishment budget will be defined to deliver positive change. We enjoy the challenge of a refurbishment. There’s something very satisfying about making an interior work better for everyone.