Harvesting Nature for a Regenerative Built Environment

Bio-grown materials are shifting the centre of gravity within design, from extraction and manufacture towards cultivation and care. Instead of digging deeper into finite resources, designers are beginning to harvest nature, working with living systems that grow, regenerate and adapt. This nature-first mindset reframes material production as something closer to agriculture than industry, where soil health, local ecologies and time become part of the design brief.

Across Europe, a new generation of projects is demonstrating how crops, fungi and overlooked plants can be transformed into viable materials for the built environment, offering a glimpse of a future where walls, surfaces and structures quite literally grow from the ground up.

The recent Fibres of Renewal project captures this shift with refreshing clarity. Working with Nieuw Zwanenburg, 25 third-year Product Design students from the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam have turned to miscanthus, a fast-growing fibrous crop cultivated on Dutch farmland, as both material and message. Their research asks a deceptively simple question: what if the infrastructure of tomorrow – viaducts, roads, locks – could be built from crops harvested locally?

Miscanthus becomes a vehicle for exploring regeneration rather than mere sustainability, inviting students to see themselves as part of a living system. Through hands-on experimentation, they translate stalks and fibres into boards, composites and sculptural elements that have architectural potential.

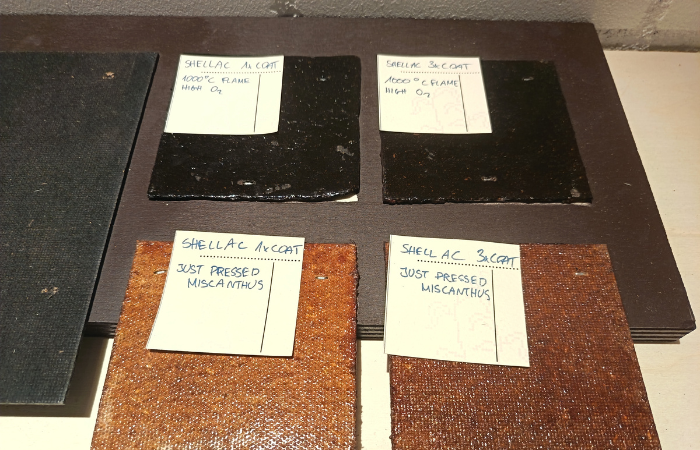

Igor Jakubowski’s Elephantiles seek to create grass panels that can be used externally, not least in wet conditions. By experimenting with charring techniques akin to Shou Sugi Ban, and applying and dissolving beeswax, the designer has synthesised a shellac finish. This imprevious layer elevates the biomaterial to a waterproof surface, which has the potential to be upscaled and produced as industry standard sized panels.

Design duo Marie Marg and Dylan Cometa van Wingerden process the miscanthus further still, pulping and blending it with an array of other ingredients in an undertaking that borders on baking. Once again, beeswax plays a part, along with linseed oil, cornstarch, coal and allium, to name a few. The investigation, Unpapered, has deployed a rich mix of paper-making experimentation, with a series of interesting material outcomes that lend themselves to packaging applications in particular.

The Nettle Project extends this bioregional thinking into a single, resilient species: the stinging nettle. Often dismissed as a weed, nettle is reframed as a multi-valorised crop with ecological, economic and cultural potential. Initiated by Iepe Bouw, a graduate from Wageningen and Delft University, the project explores how design can re-root us in our local ‘lifeplace’ by rediscovering native resources.

Nettles are remarkable remediators, improving soil health while offering spun fibres suitable for textiles, as well as teas and bio-based products. By harvesting nature in this context, the project is not about monoculture exploitation but about working within ecosystem boundaries. Bouw’s research connects bioregionalism with regenerative textiles, proposing nettle as a viable Dutch-grown fibre that can replace more resource-intensive imports.

The startup arm of the project develops a business case around multi-valorisation, ensuring every part of the plant is used, from stem to leaf, within the limits of what the ecosystem can sustain. The result is a material narrative that blends craft, ecology and entrepreneurship. Here, harvesting nature becomes an act of cultural repair as much as material production, transforming a marginal plant into a symbol of resilient, place-based innovation.

At the other end of the spectrum, MycoWorks shows how bio-grown materials can scale into high-end interiors without losing their organic soul. Its flagship material, Reishi™, is grown from mycelium and refined into a supple, leather-like surface with remarkable consistency. Unlike traditional leather or synthetic alternatives, Reishi™ is cultivated rather than manufactured, its form shaped by controlled growth conditions. This is harvesting nature with laboratory precision, where fungal networks are coaxed into architectural panels, tables and screens.

The material’s tactile richness and subtle patterning speak to its biological origins, while its performance meets the demands of contemporary interiors. Collaborations with designers and heritage ateliers demonstrate how mycelium can be integrated into wall panels, furniture and collectible objects, bridging craft savoir-faire and biotech innovation.

MycoWorks positions Reishi™ not as a novelty but as a serious contender for luxury applications, proving that bio-grown materials can satisfy both aesthetic and industrial criteria. The narrative is one of translation: turning a living organism into a stable, beautiful surface without stripping away its natural character. In this context, harvesting nature becomes an ongoing partnership between biology and design, where growth replaces extraction and material production becomes a form of stewardship.

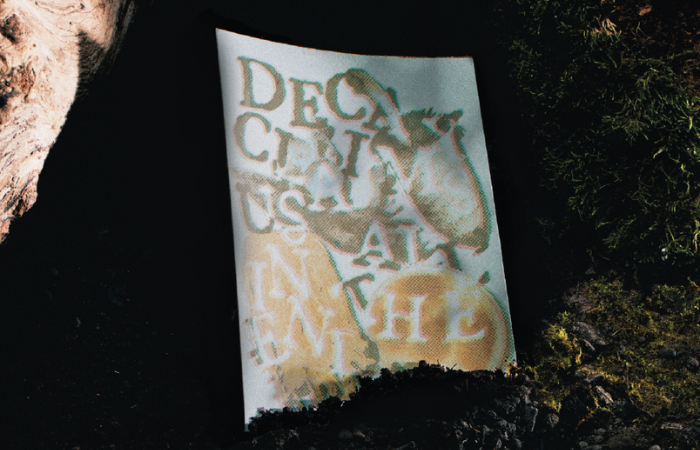

GROWinK shifts the bio-grown conversation from fibres and surfaces to the very act of marking and messaging. Every year, billions of square metres of printed material made with petroleum-based inks end up in landfill, locking toxic pigments and synthetic polymers into the waste stream. GROWinK proposes a radical alternative: living bio-inks grown from fungi and bacteria that actively participate in a regenerative life cycle.

The system harnesses the natural symbiosis between these organisms. Fungi supply vibrant pigments drawn from spores, mycelium and fruiting bodies, replacing fossil-derived dyes with colours cultivated through growth. Embedded within the ink are dormant bacterial spores that remain inactive during use, but awaken under landfill-like conditions of warmth and moisture. Once activated, they secrete enzymes that break down synthetic polymers in textiles and printed substrates, accelerating biodegradation and supporting mycoremediation.

In material terms, this is harvesting nature at a microscopic scale, turning biological processes into functional performance. The idea of print permanence is deliberately overturned. GROWinK ’s living prints are designed to communicate briefly, then evolve and disappear, mirroring natural cycles of growth and decay. Impermanence is not a failure of durability but a design feature, reframing ink as an active agent in waste reduction. It invites designers to think of graphics not as static overlays, but as temporary participants in a regenerative material loop.

Together, these projects map out a compelling trajectory for bio-grown materials. From miscanthus fields and nettle patches to mycelium labs, they reveal a design culture that is learning to cultivate rather than consume. Harvesting nature, in this emerging paradigm, is not about taking more from the earth, but about aligning production with regeneration, and allowing the built environment to grow in dialogue with the landscapes that sustain it.