Lifeblood at MUNCH Oslo: Nissen Richards Studio Designs Exhibition Exploring Munch’s Relationship with Medicine

A exhibition that positions fascinating historical objects from the world of medicine alongside contemporary artworks by Edvard Munch is now open at MUNCH, Oslo. The exhibition, curated by Allison Morehead and designed by Nissen Richards Studio (exhibition and graphic design) is called Lifeblood – or ‘Livsblod’ in Norwegian. Running until September 21st, the exhibition considers Munch’s relationship with medicine throughout his lifetime, featuring a chronological approach with different themes coming into focus in each section.

Lifeblood juxtaposes Munch’s art with medical objects and images, such as a baby incubator, glass sputum bottles, vaccine equipment, archival photographs and nursing badges. Together, the artworks and historical items ask provocative questions about modern experiences of health and illness, birth and death and the giving and receiving of care.

Through Munch’s powerful and often visceral work, visitors are invited to feel the universal experience of having a vulnerable body, to think about medicine’s promises to heal ills, and to consider their own experiences of sickness, disability, and health.

Lifeblood at MUNCH Oslo

Historical Background:

When Edvard Munch was born in 1863, very few people in Norway or elsewhere were born or died in a hospital. By the time of his death in 1944, hospital births and deaths were rapidly becoming standard in many places in the world. The artist drew inspiration from his own experiences of sickness, health and the medical environment, as well as those of his family, friends, patrons and various medical practitioners. Both the artist’s father and brother were doctors, although his brother sadly died of pneumonia shortly after completing training.

Munch referred to his own art as his ‘lifeblood’, a kind of medicine that could provide a ‘healthy release’ for both him and his public. Munch saw himself as a sick man as well as a healer and this self-image was deeply rooted in his personal experiences, with both he and his loved ones suffering at various times from chest diseases, mental distress and other afflictions. The artist was also deeply affected by the early death of his sister Sophie, aged just fifteen, from tuberculosis.

Design Approach:

Two different visual languages define the exhibition. First, the straightforward thematic language of the show’s content, expressed in the chronology of the exhibition and through the orthogonal lines of the gallery itself, representing the harsher environment of the hospital experience. As a counterpoint, a curved language runs through the exhibition’s central showcases and furniture, acting as a companion to guide the visitor. This represents care-giving, as well as reflecting the curves of the human body.

The two languages are also represented through the materials selected for the exhibition, as well as its colour palette. Colour helps define each thematic environment, whilst also being representative of the human body, both inside and outside. Surgical instruments inform the metal inserts in the showcases and display tables.

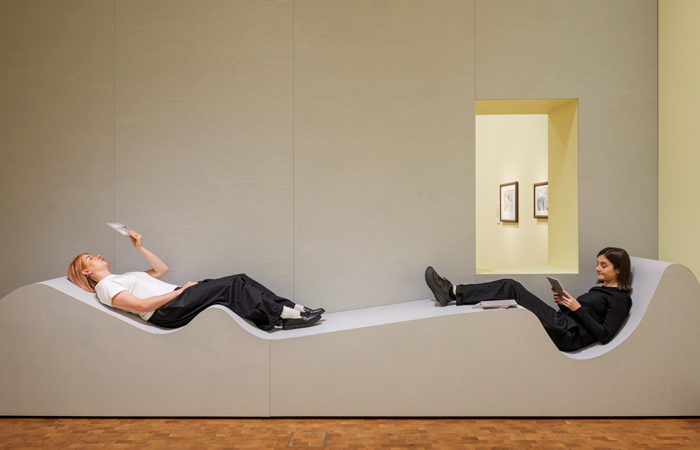

Stand out furniture item where visitors can sit or lie to contemplate content

Pippa Nissen, Director of Nissen Richards Studio commented:

“We greatly enjoyed working with Curator Allison Morehead on this project. Allison’s vision was for a show that gave equal weight to the objects and to the paintings, and we developed a language of display with her that made the objects support the story. Along with the strong, corporeal colour palette for the walls and graphics, we developed furniture designed to make visitors feel aware of their bodies, and the way that they are sitting, so that they question the objects and content in a different way. We worked with contractors to prototype furniture that is really bespoke and able to support unusual perspectives and different ways of viewing the objects.”

Exhibits include Munchs death mask

The bespoke furniture and benches, prototyped and thoroughly tested for suitability and comfort, are made from stained ply. Six varieties of seating were designed to position the body in different ways, from classic benches and benches with arm or back supports to full-length, ergonomic seats, which hint ambiguously at both relaxation and medical examination and were inspired by images taken at a sanatorium. Panels holding transcripts of letters by Munch sit at the end of these.

The exhibition took accessibility into account at all stages, with specific approaches including freestanding vitrines, so that wheelchair users can sit easily beneath and look down at the content as well as turning room for all wheelchair-users between showcases. There is also a range of different heights of seating throughout. Eye levels were considered from an inclusivity standpoint for all paintings and exhibits, as well as for wall-mounted vitrine objects, as were font sizes for the hierarchy of information on all panels and labels.

The Wellness and Tourism section looks at recuperation and vices away from home

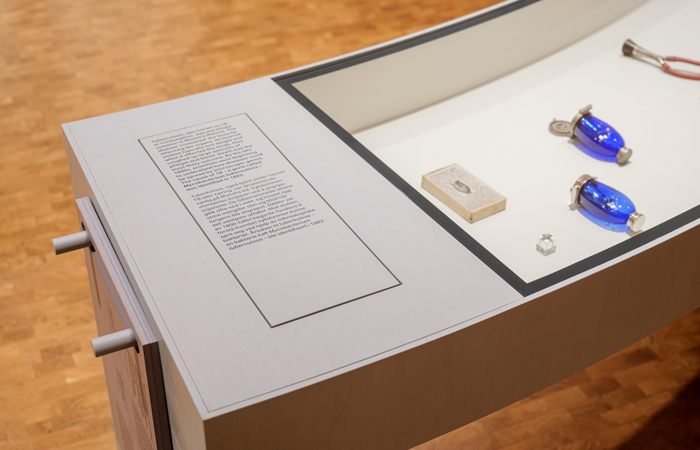

Amy Kempa, Nissen Richards Studio Associate explained of the approach to object display:

“Objects are either displayed in freestanding, purpose-built showcases in the centre of the space or are else set inside existing framed showcases within the full depth of the modular exhibition walls. The object showcases display their contents in a very simple and non-hierarchical way, making clear that these are not artworks. Window apertures offer critical viewpoints between thematic environments, allowing visitors to gain a sense of the journey to come. These also create new and intriguing cross-chronological associations.”

Objects and artworks for the exhibition were sourced from multiple places, including MUNCH’s own collection; National Museum, Oslo; Teknisk Museum, Oslo; the Wellcome Collection, London, UK; the German Hygiene Museum, Dresden; the Musée des Moulages, Paris, France; and other regional museums and private individuals in Norway, Denmark, and beyond.

Design Walk-through:

Arrival

The red-painted arrival space features a dramatic title wall with blood-red lettering, creating a high-impact arrival moment for visitors. A sloping seat protruding from one end of the wall allows visitors to sit, pause and take in the exhibition’s introductory theme. The first artwork on display – ‘On the Operating Table’ – is also highly dramatic and lets visitors know at once that the viewing experience will be both intense and at times challenging.

Exhibition and Graphic Design by Nissen Richards Studio

The story behind the opening painting is directly autobiographical: in September 1902, a doctor was called out to a cottage in the coastal village of Åsgårdstrand. Edvard Munch’s left hand was covered in blood, a bullet having struck his middle finger. The shot was fired – likely by Munch himself – during an argument with his lover, Tulla Larsen. The artist is transported back to Oslo for X-rays and surgery at Rikshospitalet, Norway’s national hospital. Soon afterwards, Munch begins the painting, a self-portrait inspired by this traumatic and painful event. In the painting Munch shows himself as a vulnerable patient, attended by faceless doctors, and observed by spectators. A deaconess nurse holds a bowl of the artist’s ‘lifeblood’, which spills onto the canvas.

This area also contains a vertical vitrine showcase, set into one of the gallery’s modular display walls, which holds a deaconess’s uniform, complete with the white cap awarded at the end of a nurse’s training, as well as the original X-Ray of Munch’s hand injury and a painting entitled ‘Hospital Ward’.

Family Medicine

‘Disease and Insanity and Death were the black Angels that stood by my cradle.’ – Edvard Munch

Medical objects displayed simply making clear these are not artworks

The second area, which is domestic in scale and painted in a dark aubergine-brown, looks at medicine in a family context and in particular at birth and infancy. It examines attitudes of the period towards medicine and early vaccinations and includes a chair from the Munch family home, set on a plinth, as well as a curved bench with armrest support and integrated pick-up mediation. Munch family letters and diaries of the day are full of details about medical treatments, trips to pharmacies, childcare, and nutrition advice.

As well as artworks, exhibits include a human skeleton used for anatomical training, on loan from Teknisk Museum, Oslo. A knowledge of anatomy was extremely important for both artists and doctors, whilst the skeleton as a motif is often found in Munch’s artistry. A second inset wall vitrine displays typical products of the time to be found at a chemist (Apothek).

Interesting and varied seating uses a curved design language throughout

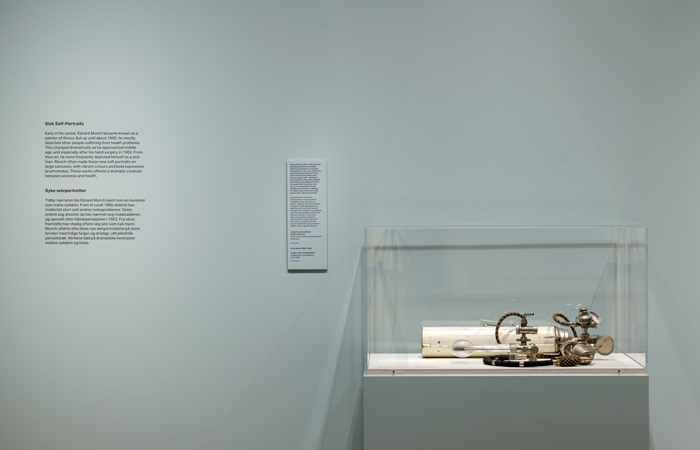

Sickness and Death

TB (tuberculosis) was the great killer of the period and the third area looks at the dominance of the disease and at available treatments. Edvard Munch was deeply affected by the early deaths of both his mother and sister from tuberculosis, and by his own experiences of chest disease.

The section is painted in a green-brown shade and features multiple versions of Munch’s well-known motif, The Sick Child, including the stunning first version of the painting on exceptional loan from the National Museum, Oslo. The harrowing subject matter is accompanied by a seat with a high back support, offering literal back-up, with the seat directly adjoining a showcase. At one end of the bench, headphones are installed, which visitors can use to listen to an audio narrative about The Sick Child. At each end of the display case, text panels contain introductory information about tuberculosis and germ theory. The panels – as with all text in the exhibition – is in both Norwegian and English. Objects in this section include a ‘Blue Henry’ glass sputum bottle, which was used for tuberculosis sufferers to spit into.

Munch artworks in the Family Medicine section

The Gender of Melancholy

This room has light blue walls and a 2.7m curved bench with an armrest and integrated magazine rack. The bench extends into a tabletop where a loom is placed as a tactile part of the display.

The subject matter of this section is the differing treatment afforded to women and men when it came to mental health in the artist’s lifetime, both reflecting and reinforcing the prejudices of wider society. Melancholic (and ‘hysteric’) women are often shown in institutions, as figures of pity and sympathy. Melancholic men, on the other hand, often appear in contemplative states of mind associated with artistic genius.

Multiple versions of Munchs The Sick Child

Self and Technology

Area five, painted light blue, is arranged around a fractured circle, made up of two long-curved showcases and a backless bench. The oculus form relates to eye disease, with eye health exhibits included in the displays. The section’s content relates to the fast-moving developments in health technology in Munch’s era, from incubators, X-Rays and microscopes to modern contraceptive technology. The downsides of rapid change are examined too, from the increased spread of diseases that accompanied speedier transportation to the pseudo-scientific eugenics movement and its political exploitation to limit ‘unwanted’ population growth.

Exhibits include Blue Henry glass sputum bottles for TB sufferers

This section also sees a shift in Munch’s subject matter, from the illness of others to a new focus on himself as the sick man at the centre of his works.

Wellness and Tourism

This yellow-painted area explores Munch’s lifelong fascination with the vices and excesses of the big city, as well as the seaside towns, spas and sanatoriums where he could recharge and restore his health, though the lure of casinos was always present, with the polar pulls of alcohol and vegetarianism on the artist also touched upon.

Seating here includes curved bench with armrest

The area is also home to the exhibition’s most stand-out piece of bespoke furniture: a long, wave-shaped bench where two people can sit or lie to contemplate the content or read the content boards associated with the section’s theme.

Great Art for Great Doctors

The penultimate area of the exhibition examines Munch’s relationship with doctors, as both friends and patrons, as well as examining the artist’s grief over the death of his doctor-father in 1889. Painted in a dense mid-brown, the space features exhibition walls set in a wide V-shape, containing one see-through aperture, with a bench and arm-rest to one end. Exhibits include a hearing aid which belonged to Munch’s sister, Inger, and Munch’s death mask, moulded in plaster of Paris from his face, made shortly after his death in 1944. The mask is mounted invisibly, as if floating in darkness.

Munch became to include himself as a sick man in his paintings as he got older

Care

The exhibition’s final section occupies the other half of the same, larger space and focuses on caregivers and the act of caregiving. During Munch’s lifetime, caregiving shifted from the home to the hospital and from the private realm to the public sphere.

View back towards Self and Technology section

Curator Allison Morehead commented on the final exhibition:

“The response from MUNCH staff, the press, and the broader public has been overwhelming and extremely moving. People have said that they can feel their body in a new way, or that they somehow feel newly in their bodies. I have heard people speaking to each other in the exhibition – semi-publicly, in other words – of their own health experiences. They have said that the exhibition feels somehow both very large and important but also intimate, comfortable, and not overwhelming. All of this is dependent on the design and its careful calibrations. People are moving in the space with the curves, reacting to the moods of the colours, enjoying the vistas and views through the openings, and making decisions about how much or how little text they want to take in. One of my favourite comments is that despite the subject, the exhibition feels surprisingly life affirming.”

Painting of mother and syphilitic child

In an added tribute to the success of the collaboration with Nissen Richards Studio, Allison Morehead added, “I cannot imagine that another firm would have taken up and explored the curatorial concept with such care and attention to detail.”