Jim Biddulph & Rob Nicoll, Chip[s]board in Conversation

There have been countless material innovations over the past decade, with big brands, independent design studios, graduates and students all getting in on the act. The desire to create new, never-seen-before materials has gone hand in hand with the burgeoning of both industry-focused material libraries and universally available social media platforms, which offer the opportunity to showcase and discover such materials. What’s more, the appetite to reuse waste materials and products inline with the post-war “mend and make do” attitude, has rapidly expanded towards a shared desire for circular-economies. In a bid to curb climate damage and create a more sustainable and cleaner relationship with our planet, many designers strive to create material alternatives that are desirable for their functionality and eco-credentials.

Co-founders of Chip[s]board, and with it, makers of an alternative bioplastic, Rob Nichol and Rowan Minkley met when studying Graphic Design at Kingston University. Whilst, the origins of numerous new materials can be traced to university campuses, the less conventional setting of a traditionally 2-D course highlights the depths to which the desire to reimagine materials has spread. Serendipity played its part, as not only did both of the then-students realise that their projects were producing excess waste from which they could make more work but Rowen’s part-time job as a chef also presented an opportunity. The pair realised that food waste, notably that of potatoes, could be re-processed to create a form of bioplastic and with it Parblex was born. Roll forward to the present, and you find a team of 7 operating from an office/lab facility in Leyton and a working relationship with one of the largest producers of potatoes, McCain. I caught up with Rob to find out more about how that came about and what it means for the studio as well as finding out more about their circular-economy approach to material manufacturing.

JB: Let’s start at the beginning of the manufacturing process, or rather, let’s start with McCain. Your raw materials are potato waste that you collect from the frozen food company. Can you tell me a little more about the material that you start the whole process off with?

RN: When we began working with potatoes it became obvious that as we grew we would want to contact McCain. Thankfully this connection came by chance as the alumni group at Kingston University reached out to us to say that the regional CEO of McCain at the time, Nick Vermont, was also a Kingston alumnus and a meeting could be arranged. Once we were in the room with McCain one thing became apparent; that they had been looking for a solution to optimising their by-products, with Nick stating that “finding a better use for potato waste is the holy grail for the potato processing industry”.

The by-product that we take from McCain is not able to be turned into a commercial food product and, after going through their waste system, is not safe for human consumption. Instead it is used as low-grade animal food. The process at Chip[s] Board doesn’t cut off this animal food supply, instead we remove all the components that we need and leave a separate waste stream that can then be forwarded into animal food. This scenario is actually far better for the animals as it becomes a more refined, nutrient rich product and for the environment as it maximises the potential uses of the waste material.

JB: So, how do you go about transforming the potato waste? Can you say what processes are involved?

RN: At this moment in time we are unable to reveal our process. However, in an extremely simplified way, I can say that we receive the feedstock, which is a byproduct from food manufacturing and we break this down in order to find the building blocks that we need. The waste comes in several forms that are generated at different stages along the processing line. This ranges from solid peel to a more homogenous mash. Our process means that most feedstocks are usable and we can polymerise those components into a plastic. This is currently being run at lab scale with larger batches being processed constantly. We plan to open a pilot facility at the end of 2020 that would give us a larger output and facilitate the majority of the trial production runs that are currently being discussed.

JB: Can you tell me more about the applications for Parblex? What Kind of products can you make from it?

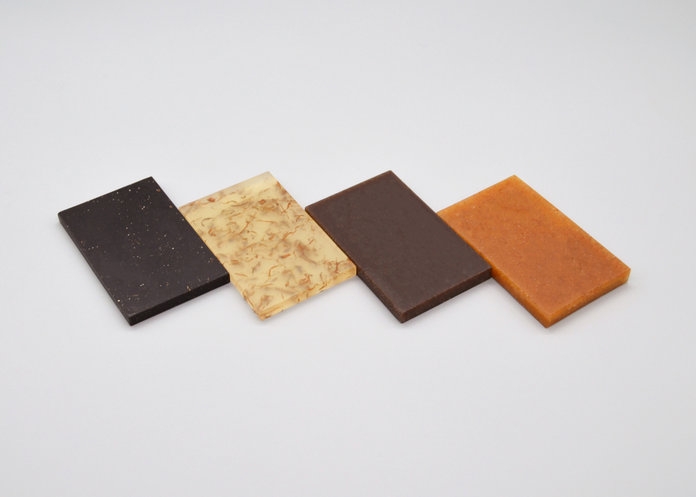

RN: Where applications are concerned, Parblex is a thermoplastic. This means it is ideal for injection molding and extrusion. To date our materials are already being sought after for a wide range of applications, with focus on the fashion and interior sectors. For example, eyewear, clothes hangers and buttons are all in the works. The versatility of Parblex being a thermoplastic means that the product possibilities are only restricted by the desired performance. For example, our material doesn’t have an incredibly high impact resistance so products such as skateboards would be less than ideal.

JB: I’m particularly interested in the “recycling” and “composting” elements of your closed loop diagram; can you explain what goes on with each in a little more detail?

RN: As a thermoplastic our material can be reprocessed by regrinding, melting and reforming. However, as we are still on a research and development stage, we are yet to test the amount of cycles that our material can go through before heat degradation begins. Where composting is involved our materials are suitable for industrial composting rather than for home food waste. This is the same as other bioplastics that are already on the market, including the compostable coffee cups and lids that are growing in popularity. The need for industrial composting is why we have developed a closed-loop system that recovers our product and re-purposes it, to take ownership of our material at all stages of its lifespan.

JB: With so many material manufacturers claiming to be “eco” and sometimes doing so spuriously, will you be looking to take the leap in seeking some form of eco accreditation?

RN: We are currently aiming to obtain accreditation through C2C as they are one of the main certifiers and are well known and respected. The backing of an organisation like C2C would give huge credibility to the work we are doing and show that we are being transparent and responsible within our process; which we are very passionate about.

JB: I guess we can’t really avoid some discussion regarding the current global pandemic; I was wondering what your view might be on how this might all affect the plastic movement we had been experiencing over the past couple of years?

RN: Well, panic buying will always have a huge effect on waste as it consists of over consumption. At Chip[s] Board we care about the plastic waste and food waste issue and panic buying effects both. Initially, the increase of buying food means an increase in the plastic packaging entering our waste streams, as well as larger amounts of surplus of perishable food waste as people buy beyond their needs. It is very easy for Covid-19 to shroud other issues but the knock-on effect of behaviour during this global event could be devastating in the long-term. As a wider society, we are already aware of the immediate pressures on our environment caused by waste and particularly plastic pollution, but now is certainly the time for people to consider the impact of their individual actions and choices as we navigate this pandemic.

Contact Chip[s] Board

Comments