Talk: Furniture & the Road to Net Zero with Modus & Dodds + Shute

Enjoy this transcript of a recent presentation and discussion on ‘Furniture and Our Journey to Net Zero’ with Lucy Arndt, Head of Sustainability at Dodds & Shute and Lucy Crane, Sustainability Manager at Modus, introduced by Alys Bryan, Editor at Design Insider, which was part of Clerkenwell OPEN.

Alys Bryan:

I’m absolutely thrilled today to be here in the Modus showroom. Modus have two decades of experience of creating award winning beautiful furniture, designed by the world’s leading designers. Not only that, but all of Modus Furniture, from start to finish, is manufactured in Somerset using renewable power. So they are able to marry international design excellence with local craftmanship, delivering furniture with soul!

Today, I am joined by two Lucys.

Lucy Crane is the Sustainability Manager for Modus. Her background was originally was furniture before, in 2015, she moved over to focus on sustainability. One of the driving forces for this move was the ambition to achieve the FISP accreditation. The work that Lucy does supports all the different sectors within the Modus team. She supports, and works alongside, the Modus design team, but also their sales team.

I’m also really thrilled to be joined by Lucy Arndt from Dodds & Shute, where Lucy is the Head of Sustainability. Lucy has over a decade of experience, not to mention a Master’s in Sustainable Development, and prior to joining the team at Dodds & Shute, Lucy worked with Ecosphere Plus as Director of Climate Solutions. Lucy led a team which achieved 40 million tons of carbon avoided through climate finance, delivered to forest conservation projects around the world, and I know that you’ll hear in their presentations more about those achievements.

Dodds & Shute is a procurement practice with a pure focus on procuring the most sustainable furniture that they can find.

It’s very fitting that Lucy is here with Lucy in the Modus showroom. Once we’ve finished, there will be an opportunity for you to ask questions. So please do think if you’ve got anything you would like to ask Lucy and Lucy.

Lucy Crane

Thank you very much, Alice. Thank you for introducing us both and thank you everybody for coming along to the showroom today.

We are here to explore the relationship between furniture and our road to net zero. And I say our road to net zero because it really needs to be a collective journey. It’s a global ambition and we need to work together to find low carbon solutions that will address rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

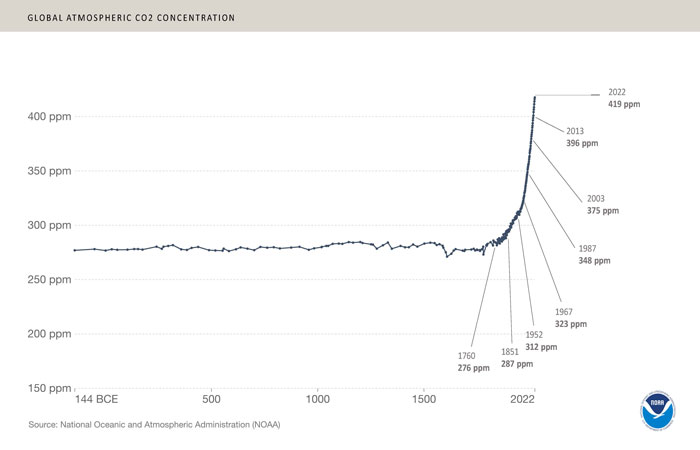

I’m sure you’re all very familiar with this graph. This line represents global atmospheric carbon dioxide levels through time. Way back before the industrial revolution, you have global atmospheric carbon dioxide levels pootling along about 276 parts per million. Then as the industrial revolution unfolds over the course of roughly 100 years and you start to see a rise. Now that rise, at this stage, is about 4% over 100 years. Then if you fast forward another 100 years to the early 1950s, we see an additional 9% rise. So that’s over the course of another century. This is where that curve starts to shoot up. So if we go right to the top of that line, the figure released earlier this year for global atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, is now at 419 parts per million. That shows a rise of 12% in just 19 years.

So it isn’t just rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, it is the rate at which they’re rising. They’re rising so fast that it doesn’t give species, and that includes humans, time to adapt, but we absolutely have to adapt to try to make the changes that we need to start flattening that curve.

Before I come onto furniture, I’d like to set out a definition of net zero. I’m going to use the science-based targets’ initiatives definition of net zero. That is a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions across scopes one, two, and three, to zero or a residual level that is consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees.

Typically, businesses targeting this standard are looking at a 90% to 95% reduction in carbon emissions across scopes one, two, and three by or before 2050. We are talking some serious, serious cuts. If we are going to make those cuts, the first thing we need to find out is where is all this carbon coming from?

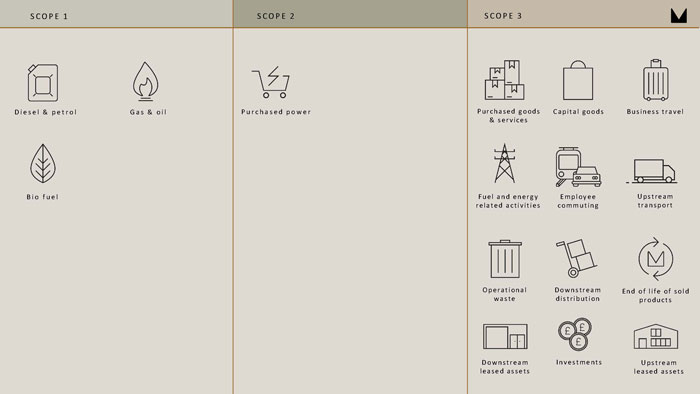

Carbon emissions are very neatly divided into three scopes. In scope one, you will have emissions that are direct to air, that are controlled by your organization. Those will be the burning of biofuel, if you use that to heat your buildings, and gas and oil for heating. Then you’ll also have the diesel and petrol that you use in your company-owned vehicles and potentially machinery. Now, scope-one emissions are unlikely to represent the bulk of your carbon emissions, unless you are an airline company or a freight company. So most people are mapping and measuring scope-one emissions, which is great.

Scope-two emissions are emissions associated with purchased power. Again, unlikely, to make up the bulk of your carbon emissions unless you are buying tons of electricity, like a foundry or Bitcoin mining or something like that. Probably all of us are measuring scope one and two, and looking at ways of reducing them.

But, the bulk of your emissions sit in scope three, and that’s true of almost all organizations. It’s typical for at least 75% of your carbon emissions to sit in scope three. If we really want to make a difference, we need to focus on those scope-three emissions.

So what’s in scope three? There are 15 emissions categories in scope three, and I’ve only put 12 on there because some of them probably aren’t going to be that relevant to many of you. But there will also be franchises, the processing of sold goods and the use of sold goods. But on here, universal to probably all of us, will be things like employee commuting and home working, business travel, investments, operational waste, downstream distribution of goods and so on.

Furniture, where does furniture fit in here? Well, it depends what your organization is doing. For us as manufacturers, it’s going to sit in emissions category one, purchased goods and services. That is going to be made up of the raw materials that we buy to make our furniture. For our end clients, for many of your clients, furniture is going to sit in capital goods, the goods that they purchase. If we are going to be really serious about reducing our carbon emissions, we’ve got to look at the materials that we are putting into our furniture and reduce the carbon in those.

So how much carbon is in furniture? I was reading somebody’s master’s thesis on the train on the way here, because I just wanted to get a bit more detail and have a look at some more studies about how much carbon is in the furniture that we put in our buildings. It was a pretty robust piece of work and the study showed that somewhere between 4% and 20% of a building’s overall carbon footprint, was made up of the furniture within it. Now these figures are based on a 15-year lifespan for a piece of furniture, and a 60-year lifespan for a building, which I felt was a bit short on the building side for sure, but that’s what they’re based on. Most EPDs are based on a 15-year service life for a piece of furniture and I will come back to this point. The lady who did her master’s on this found, and you will all, I’m sure, be finding that there is a real lack of information out there.

There just isn’t that much data, there just hasn’t been that much work done on carbon footprinting of furniture. There are many, many reasons for this. If furniture makes up a potential 20% of your buildings overall carbon footprint, then it seems odd that it’s very rarely included in a building’s whole carbon assessment. The EU consumes 10.5 million tons of furniture a year, and this is the really scary bit, it wastes 10 million tons of furniture a year. So it’s a really significant carbon burden that needs properly looking at.

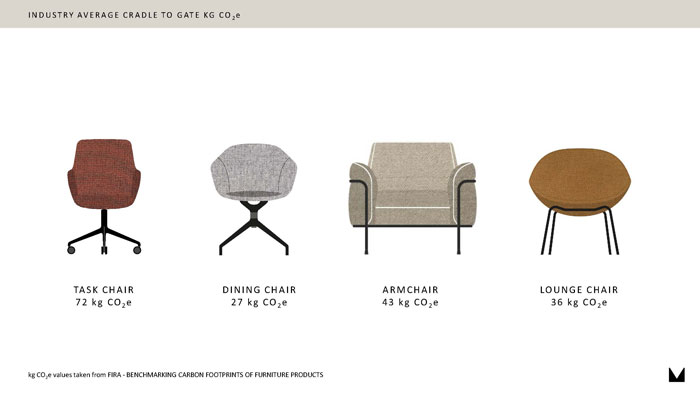

These figures on the screen here, some years ago, FIRA, the Furniture Industry Research Association, commissioned a benchmarking study into industry average values, carbon footprints of mostly contract furniture, mostly office-based furniture. This study was very small, and some of the averages were based on just two numbers. So it’s quite problematic.

When I was looking at these values, I don’t know if you can see them, the numbers right at the back, I thought, well these are pretty low. There’s also 90 kilos for a sofa, and 45 kilos for a 1,200 by 1,600 workstation. So I spoke to FIRA and asked them about the methodology behind this study that they commissioned. It turns out that all the figures are based on a cradle-to-gate assessment. When you do a cradle-to-gate lifecycle assessment, you are including things like the extraction and production of raw materials, the transport of those materials to the gate, the manufacturer of the furniture item in terms of operational waste, energy use and so on. The emissions associated with the administration carbon cost and the warehousing and so on and so forth, and the embodied carbon in the packaging. Now the piece of furniture is made, boxed, ready to go, and that’s it.

That’s really only half the story, because although the bulk of the emissions will be in the cradle-to-gate stages, what about the transport to site? What about the processing of the packaging that you’ve wrapped around that product? What about the in-use stage? There may be emissions associated with, especially if you have these sit stand desks that are electronically operated and so on. Then really significantly, what about the deconstruction phase and the end of life stage? So when we do a carbon footprint, we do a whole of life stage, so that’s a cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment and the figures will come out higher obviously.

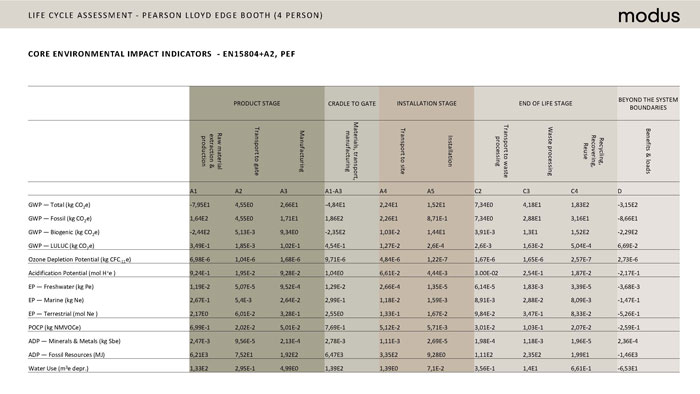

How do we calculate the carbon footprint? How do we carry out the life cycle assessment? Lifecycle assessments are very detailed, in-depth pieces of work. They are difficult to do and they take a long time. Those are some of the reasons that there’s not much data out there for furniture. That’s certainly one of the reasons that we haven’t done very many yet, but we are working our way through them. Once you’ve put all your data in, the output is a table of results like this.

If you look at the column, the white column on the left, you’ll see that this isn’t just showing us the carbon impacts, this is showing us environmental impacts across 13 different impact categories. If anyone wants to know, go for it, but probably it’s a bit boring for you. So I’m just going to say at the top, is global warming potential, and that is your carbon footprint. Right at the bottom, you’ve got water use and in between, there’s a whole host of environmental impacts.

Then if you look across each column, it represents a different life stage for that product. So a cradle-to-gate assessment will cover these first three columns. That’s the sum there, and this is what continues on beyond the gates. That’s what you’ll get, if you do a full cradle-to-grave assessment.

I have learnt nobody likes my tables, meaning they’re not very accessible. So we are working on a better way of communicating this, and I think that’s maybe a bit more accessible for people.

This really is a piece of work that we can feed back to our design team. Because when you start to see where the carbon is accumulating, you can start to drill down and find out what’s going on, why is it building up there and what can we do to reduce it?

I’m going to draw your attention to the huge amount of carbon in the materials in our Clara chair, which I will come back to in a second, but to compare it to a Bob stool. Obviously they’re made from very different materials, but when you start to grasp how the materials make a difference, and also if you just look at the packaging in the middle there, that’s a bit odd because that chair is a big chair and the Bob stool’s tiny. So why was that packaging relatively high for the Bob stool? Actually, it’s reused piece of packaging too, but we have to account for the embodied carbon in the packaging. The answer lies in the fact that this chair is packed with end caps cardboard, kind of like a half box if you like, and wrapped in, dare I say it, very thin plastic film, and the Bob stool is in a cardboard box.

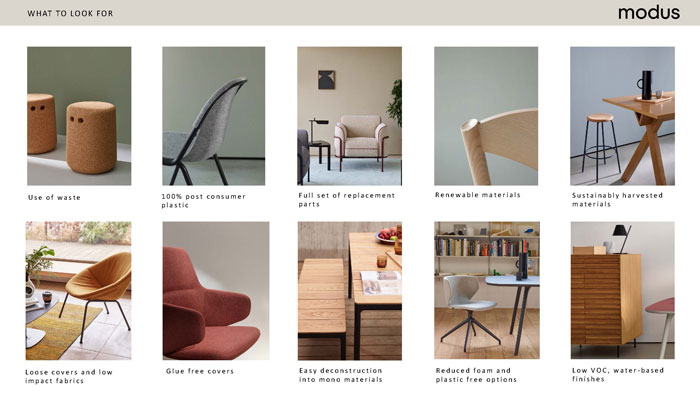

Relatively speaking, there is a lot more carbon in the packaging of the Bob stool than there is in the Clara chair. You wouldn’t think that, would you, because it’s partly plastic. The point of doing this is that you stop making assumptions and you start learning where those impacts are really building up. That’s key, because it’s only with this level of detail that we can make improvements, continual improvements to the product, the way it’s packed, the way it’s delivered, and so on. I’m not going to go into this slide in much detail, because I think Lucy’s going to speak a bit more about what you need to look for in a low carbon product. But I would say the first thing, if it’s there, look at the data. Look at the data and ask your suppliers, is this a cradle-to-grave or a cradle-to-gate assessment? But often, the information isn’t there yet. So there’s so many things to think about.

If there are three things that I would be looking for, the first would be reuse the furniture that you’ve already got. That is a terrible, terrible thing for me to say when I work in furniture manufacturing, but it’s the truth. Reuse as much as you possibly can. If that isn’t an option, then look for products that you can prolong their life, because although the carbon value in a product is the same, whether it lasts for five years or 10 years, obviously the longer you can stretch that product out, the lower the overall carbon in the long run. Current studies are accounting for a 15-year lifespan, which I think is actually quite a long time, because often refurbishment of a building would be what, seven, 10 years, something like that? But if you can find a product that you can very easily refurbish at a much lower carbon impact, that is a good place to start.

Finally, I would say to look at the materials, because it makes a very, very big difference. When we were embarking on these lifecycle assessments, and we discovered the Clara chair had such a high embodied carbon in its materials, we looked at that and 84% of the embodied carbon in the materials of the Clara chair was in the foam and the polyester wrap going around the cushions. Don’t get me wrong, this chair is great in terms of the whole thing comes apart, you can replace parts and so on. But if you replace that cushion set after five years, you are putting another 43 kilos back in. So once we’d learned this, at the time we were working on an extension to the Pearson Lloyd Edge seating which is a lot softer and dare I say chunky, thick, kind of supportive rather than the previous seating was quite firm and we wanted something that had a bit more of a domestic feel.

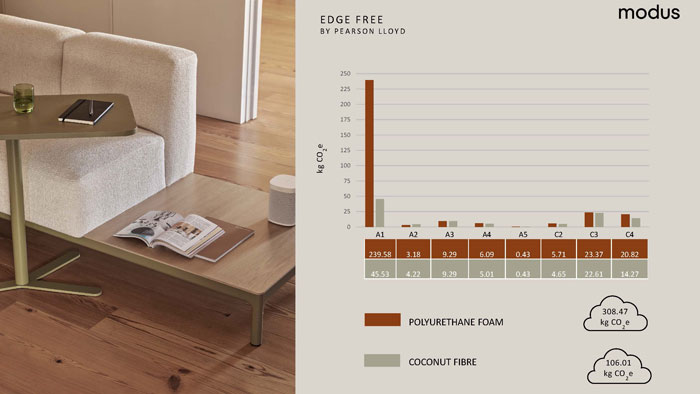

We were originally going to offer a foam version and a natural fiber version. However, once we modeled it in our software, you can see here, I don’t know if you can make out this green one, but this stage A1 is just the material stage. This chart shows you the difference when using traditional polyurethane foam versus coconut fiber and needled wool wrap. If you take out the foam, the difference in the carbon in the material stage is nearly 240 kilos when made in traditional polyurethane foam and only 46 when using coconut fiber. Throughout the whole life cycle of this sofa, you are looking at 308 kilos for a three-seat sofa versus just 106 for a coconut fiber, which is what this is. So we decided we’re just not going to do the foam one, we’re going to work to make the natural fiber one the only option, and so that’s what we’ve done.

Thank you for listening. Before I hand you over to Lucy, I’m just going to say, to sum up, I think as manufacturers, it’s our responsibility to try to provide the data that you guys can work with, and to work with our design team to design out the carbon. For most of you guys, I would say that your role is in trying to guide your customers to buying a lower carbon furniture package, and to work together to try to decarbonize the furniture that’s in our buildings. Thank you very much.

Lucy Arndt:

Thank you so much, Lucy. I found that very, very interesting to hear what is going on in terms of what a supplier is actually doing within their production to look at bringing down the carbon.

I’m going to take a little bit of a step back now to talk about, go back to kind of net zero, what does that look like. Hopefully, the aim is by the end of this, I’ve talked a little bit about some of the top tips for where to start when looking at net zero.

I think we have all seen the data on the chart that Lucy showed with carbon emissions dramatically increasing. How do we go back to our desks today, tomorrow and actually start doing something about it? What does net zero mean in practice? It started off as a planetary global goal. We know what we need to do scientifically to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement and most countries in the world have decided to commit to keeping climate change to not more than 1.5 degrees Celsius in order to avoid the most dangerous effects of climate change. That was the planetary goal. Then what? From there, that started to flow down to countries, and now to companies who are all also starting to commit to net zero. In reality this means a 90% reduction of emissions by 2050.

Various countries and companies are committing to dates earlier than that if they are leaders in the space and want to really make a difference. That might be by 2030 net zero targets or 2040 net zero targets and the latest 2050 net zero targets. In fact, to date, net zero commitments and pledges across industries and countries now cover 88% of global emissions and 90% of the global economy. That means in very high likelihood, many of your companies have made net zero targets and if not, many of your clients and their investors have made net zero targets. It’s really starting to trickle down to the point where if your company and your clients haven’t made a net zero target, they’re clearly in the vast minority. We will, in the next few years, get to the point where this is a driver with what a lot of companies are doing.

As I said at the beginning, I’ve worked on net zero for a long time. My previous job I was helping some of the biggest companies in the world take action on this. As I said just a minute ago, everybody agrees this is the right thing to do, but most people don’t know how to actually start doing it. So if you’re feeling like that, you’re not alone. Let’s look at what we can all start doing. What does a pathway to net zero actually look like? Maybe some of you have seen a graph like this before, but maybe not.

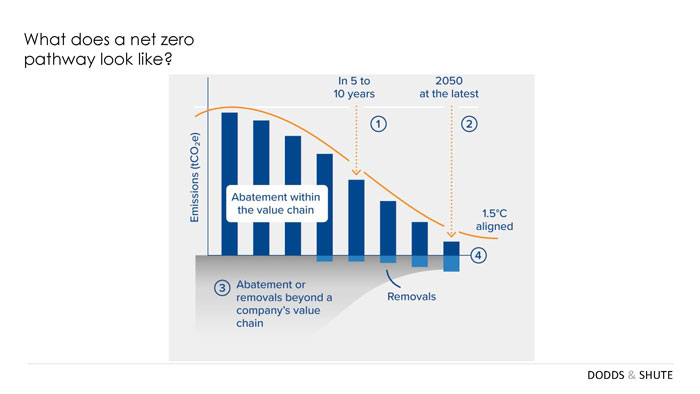

I’ll go through the numbers in order. We have number one sort of an interim target to a final net zero target. As I said, this could be 2030, ’40, ’50, or somewhere in between. Then what we start to have are these emissions coming down incrementally year on year, to make sure that we reach the final target at the end. By number two, the emissions left are what we call the residual emissions at the end. So we say net zero really means 90%, 95% emissions reductions. Well there’s that little bit that’s left, the 5% to 10%, and this is stuff that technology just will not have caught up by then. It’s impossible to reduce your emissions fully 100% to zero. There will be residual emissions and these need to be removed from the atmosphere. At the end of the day, we’re talking about net, that means what goes in comes out and it’s net zero. This is number four on the graph.

Why is this important? I think it’s really important just to visualize what it means year on year has to happen. It means to reach net zero, we all need to be looking at taking these bite size chunks out of your carbon impact, your client’s carbon impact, your projects carbon impact over time, to meet these interim targets to meet the net zero goal. That’s kind of the big picture, how we get on this journey, what it kind of looks like. What can we be doing now to make that happen? Where to start? My advice, and Lucy actually really talked about this quite a lot, so I think you’ve already heard a bit of this message, but we’re talking about carbon here. In order to reach a net zero goal, you really need to know where that impact is coming from. You need to understand what that footprint is.

Data is so important, and I would say that’s the first place that we all have to start. Something that’s said a lot in this kind of space is you can’t manage what you don’t measure. It literally is saying that. If you want to start reducing your carbon, you got to know where it comes from. We’re a procurement agency. We work with hundreds of suppliers, hundreds and hundreds of suppliers, and we launched a sustainability audit about four years ago to start gathering data from our suppliers across key sustainability metrics. So we’ve been gathering tons of data over several years, and I can tell you that real carbon data, kind of as Lucy alluded to, is not common.

That brings us up to the first stumbling block. If we can’t assess what the true carbon footprint is of the furniture that we’re buying, that obviously raises a challenge. I would say it’s a call to action to all of us in this room as majority people here are not suppliers or manufacturers, is we need to start asking these questions of the people that we are buying our furniture from. It’s excellent to see brands like Modus doing this work, because we will soon get to a point where everybody needs to be doing this.

If we can all start having those conversations with the people that we’re working with, I think that’s where we all need to start. Because as I said, we really can’t start reducing emissions till we actually know where they’re coming from and what the true emissions are. I would also say I’m a bit of a carbon nerd. So I think carbon is extremely important, but I would argue that carbon is a great proxy. It’s a great proxy for wider environmental impact. Yes, if you have an EPD, as Lucy said, that gives you 13 impacts, such as land use and water, but that is a very detailed look at the impact of furniture, and many, many people just aren’t able to get there. So carbon is, as I said, a great proxy for understanding the wider impact of a piece of furniture, of a building, of really anything. It’s something that we all measure, we all have targets against, globally, et cetera, down the chain as I mentioned. Carbon data I think is key. We often have suppliers speaking to us and saying, “Look, we’re really interested in sustainability, we really want to do something, but where do we start? What are your clients asking for? What should we focus on?”

I would say carbon. I think hopefully you’ll agree, that actually getting the real data is really critical. This other piece on where to start, materiality, I don’t know how many of you have heard of this concept, but in the sort of sustainability world, it’s used a lot. What does materiality mean? Lucy also talked about the benchmark data that’s been done across the industry. I just want to go back to that quickly. Yes, there are some challenges with how extensive that data is, but it does give us a general picture of a whole range of products. That data shows that, and this might be intuitive, but data proves that some of the highest carbon impact and products that we all probably work with frequently, are things like sofas, mattresses and task chairs are also really high up there.

The concept of materiality is, if you are working on 150-room hotel, you should be focusing on the products that have the biggest impact for the climate, which means, in this case, the mattresses in that room or the sofas in that room, not the wooden wardrobe that are in all of those rooms. Similarly, if you’re looking at an office space, task chairs should be the first thing that you look at, rather than the desking, because comparatively, those products are the ones that have the biggest carbon footprint and therefore if you spend your time, your resources, whatever else to focus on one thing for one project to start making those bite-size chunks come down, start with the highest impact products, because that’s where you’ll have the greatest impact.

I think that is really, when I sort of say it out loud, that is a very basic concept. But again, it goes back to data. If we don’t know what the products that you’re working with your clients are that have the biggest impact, it’s really difficult to know where to start. As I said, you want to have the biggest bang for your buck. Really understanding the data, what most material is really the best, most practical place to start.

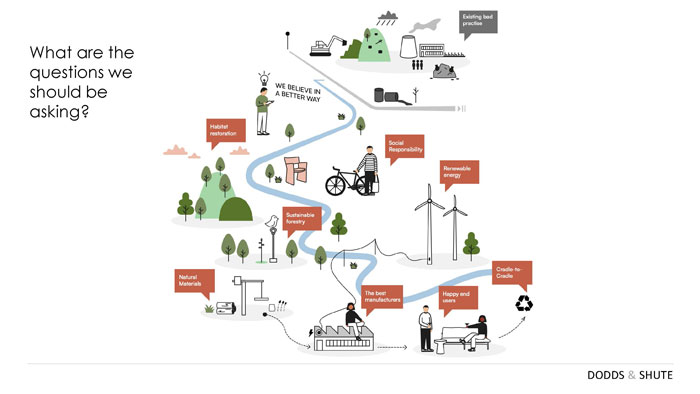

What are these questions that we should be asking and what are the conversations that we should be having? This is really, I guess, in the absence of data that if we don’t have that core carbon footprint analysis of the products that we are buying and supplying, what are the characteristics that we can look back to, to understand if those products might have a greater or lesser impact on the climate?

I’m just going to go through some really key areas that I think we should all be looking at and keeping at the top of our priority list, but also of course continuing to have the discussions with the actual manufacturers who are making those products. This is a little bit of a journey diagram, I guess you could say. But the idea is that… Bad practice is I’m not going to shout out what that might be, but I think we all kind of know that what we’re currently doing across the world isn’t really working, we’ve got to move to a new world. What are some of the things we should really be looking at? Knowing the providence of your goods, this is what I’m talking about in terms of asking those questions, really understanding what products are made of, where they’re made, who’s making them and how they’re made is critical.

Key things to look out for are things like the use of natural materials as Lucy kind of was talking about with some of their products. And why is this? Things like wood as a natural material, as you probably all learnt in school, photosynthesis takes carbon out of the atmosphere and stores it in the wood or the plant that’s being grown. It’s basically the oldest carbon technology that we have. It does what we are trying to spend billions of dollars to create incredible new technology to do. The use of natural materials can actually be what we call carbon sink. Carbon is stored in this wood. And on an EPD, it can actually subtract carbon from the overall calculation. The use of natural materials I think can often be kind of seen as a cliche thing like, “Oh, we really want to be thinking about the environment and being more sustainable.” But there’s a reason for that. It’s not just because wood makes you think of trees, it’s because it has a significantly lower impact on the environment.

This goes for alternatives to foam, as Lucy was talking about. So the use of coconut fibers or sheeps wool. It all has a significantly lower impact on the environment from the production and the actual generation of that material. But not only from the production side of things, at the end of life, natural materials are significantly better in terms of what happens at the end of a product’s life cycle. Natural materials, as we can all assume, hopefully break down. They can biodegrade, decompost, rather than plastic, which will stay in existence for hundreds and hundreds of years well beyond us. Something also to think about is when natural materials are blended with non-natural materials, it essentially renders that natural material, I guess the same as the non-natural material. Fabrics is is a good example. If you have a natural fiber blended with a plastic fiber, that natural fiber is no longer of much value. Blended materials is a really tricky one.

I would say there are some exceptions to the natural material point. While I talk about fabrics, cotton is a really interesting one. Cotton has a massive water usage, but also pesticide usage, particularly if it’s not organic, and pesticide is a really high carbon impact for that product. There are some exceptions to the rule, but in general, natural materials. Let’s continue kind of on the thought process of end of life. So there are loads of different aspects we can think about for this. One piece of it, as Lucy said, is the actual lifespan of that product. That often correlates to things like warranties. If a product only has a two-year warranty, that makes a very different statement from if a product has a 10-year warranty. We can expect that that product will actually be around for a longer period of time, and that’s much better for the environment of course.

Similarly, for end of life, if products are built for disassembly, there are some certifications around this. You’ve probably heard of cradle to cradle. That is the concept of a product is designed and built with the end of life in mind, and can, for example be easily disassembled. The individual parts can either be reused, properly recycled, and fully dealt with at the end of life. As I said, this is where blended materials are really difficult, or products that have glued fabric on furniture rather than having a zip-off-able cover. End of life is a really key one that I think is something that you can all be looking for. And another couple of bits that I’m sure we’re all well aware of, but just to mention of course energy use is a really big one in terms of the production of any furniture. And I think this has an interesting correlation to where products are made.

We talk a lot about local production, and that can be good from many sides. It can be better in terms of supporting the local economy, maybe there are better workers’ rights in different parts of the world, perhaps different environmental regulation. But something to think about is also the energy makeup of different countries. For example, in the UK, I looked it up this morning, today our percentage of renewables was about 24% of our grid connection in the UK, and about 13%, I think was also considered low carbon and coal was only 3% as of this morning. But for example, in countries like Poland, they are still vastly based on coal. That is their grid energy. There are parts to local production that I think aren’t as talked about, but I think grid and energy is something interesting to think about.

That’s not to say that of course factories can have their own power being generated on site. Onsite renewables is really an increasing trend, and of course is kind of the best of the best. But having solar panels, using scrap wood to fuel the factory, steam, there’re all sorts of things that are currently being used. But I think those are some of my top areas that, in the absence of data, we should be asking these questions and looking at these characteristics of furniture.

I thought I’d give a really quick summary, and then I think we’re just on into Q&A. But my top tips are really ensure what your net zero target or your client’s net zero targets are, and what that actually means annually or by project by project, and those incremental bites to get down to zero. Focus on what can we do here to bring down that curve. For me, this starts with data and asking the questions and starting to have the conversations. From that, it is what is the most material impacts that your jobs are having and how can you start to focus on that. And the way that you do that, is either from the data or by looking at these key characteristics.

Alys Bryan:

Thank you so much, Lucy. Thank you so much. Lucy, Thank you so much to everybody for joining this talk today. This has been a Design Insider talk, hosted by Modus, and part of our Clerkenwell OPEN event.